Uveitis

Peer reviewed by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 10 Feb 2026

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Uveitis article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is uveitis?

Uveitis is inflammation of the uveal tract, with or without inflammation of neighbouring structures (eg, the retina or vitreous). The term covers a diverse group of conditions leading to the common end-point of intraocular inflammation, and which have been estimated to cause approximately 10% of severe visual impairment. This makes uveitis one of the leading causes of preventable severe visual loss in developed countries.1

See the separate Chorioretinal inflammation and Choroidal disorders articles for additional detail on posterior uveitis.

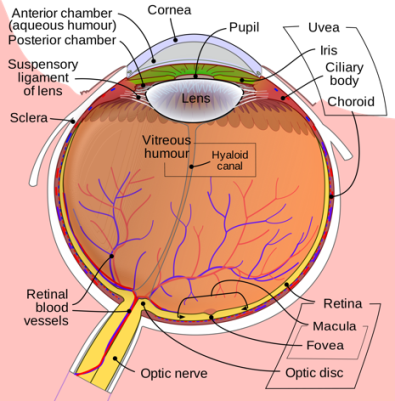

Anatomy of the uveal tract

Back to contentsThe uveal tract is the pigmented middle layer of the three concentric layers that make up the eye, lying between the sclera (superficial to it) and the retina (deep to it). It consists of the iris, ciliary body and choroid. The name comes from the Latin uva, meaning grape; it is possibly a reference to its purplish colour, wrinkled appearance and grape-like size and shape.

Human eye schematic

Attribution: by Rhcastilhos, via Wikimedia Commons

Continue reading below

Types of uveitis (classification)2 3

Back to contentsAnatomical

Uveitis may be unilateral or bilateral. It is classified by anatomical location of the inflammation, by inflammatory appearance and by chronicity:

Unilateral conditions are more commonly acute and can be infectious.

Bilateral conditions are likely due to chronic, systemic conditions.

Uveitis may be anterior, intermediate, posterior or panuveitis. More anatomically descriptive terms have been used in the past and persist in scientific literature and usage.

Anterior uveitis describes inflammation of the iris. It is also referred to as iritis, iridocyclitis (if there is also ciliary body involvement) or anterior cyclitis (if only the anterior portion of the ciliary body is affected).

Intermediate uveitis affects the vitreous and posterior part of the ciliary body. It is also referred to as pars planitis or posterior cyclitis, or as hyalitis when the inflammation involves only the anterior portion of the vitreous.

Posterior uveitis describes inflammation of the choroid. It is also referred to as choroiditis, or as chorioretinitis if the retina is also involved. It may also affect the retinal blood vessels, giving rise to retinal vasculitis. Posterior uveitis is further defined as being focal, multifocal or diffuse, depending on the nature of the inflammatory lesions seen on the fundus.

Panuveitis describes inflammation throughout the uveal tract.

By duration and course4

Acute conditions typically have an abrupt onset lasting several weeks. If left untreated, an acute condition can develop into a chronic cellular response.

Chronic uveitis is active uveitis that persists longer than three months. It is associated with a high incidence of vision-threatening complications, such as cataract, macular oedema and glaucoma, which may cause irreversible visual loss:3

Granulomatous inflammation vs non-granulomatous5

Keratic precipitates (KPs) are clusters of white blood cells found on the posterior (endothelial) part of the cornea, resembling little white spots. Those which are larger and greasy looking are referred to as mutton-fat KPs. Uveitis is classified by the morphology of the KPs into non-granulomatous (small KPs) and granulomatous (mutton-fat KPs):

Non-granulomatous uveitis is more common. It is usually anterior and has an acute onset accompanied by a cellular reaction in the anterior chamber, involving smaller cell types (lymphocytes) than those in granulomatous inflammation. It is most commonly idiopathic or due to HLA-B27 involvement.

Granulomatous uveitis is usually chronic. There are large inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber. It is often associated with systemic conditions and autoimmune reaction, or arises from the host's immune response to a systemic infectious process, such as syphilis, Lyme disease, tuberculosis or herpetic viral infection.

Causes of uveitis (aetiology)

Back to contentsThe various forms of uveitis represent the common end result of multiple underlying causes of ocular inflammation. These include:3

Inflammatory - due to autoimmune disease.

Infectious - caused by known ocular and systemic pathogens.

Infiltrative - secondary to invasive neoplastic processes (sometimes referred to as masquerade syndromes). Intraocular lymphoma may present as a chronic uveitis in older patients. Intraocular tumours may also occasionally present with posterior uveitis.

Trauma - a common cause of anterior uveitis. Sympathetic ophthalmia (sometimes referred to as sympathetic ophthalmitis) is a rare form of bilateral panuveitis in response to trauma or surgery to one of the eyes. See also the separate Sympathetic ophthalmia article.

Iatrogenic - caused by surgery, inadvertent trauma, or medication (eg, rifabutin, cidofovir).6

Inherited - secondary to metabolic or dystrophic disease.

Ischaemic - caused by impaired circulation.

Idiopathic - when evaluation has failed to find an underlying cause. Most uveitis, particularly anterior uveitis, is idiopathic.

Immunosuppression causes a particular risk of infection-related uveitis.

In Britain, sarcoidosis is the most common systemic disease that presents as chronic uveitis. In Japan, Behçet's disease is the most common systemic disease associated with chronic uveitis and, in other parts of the world, it may be tuberculosis.4

Continue reading below

Pathophysiology3 7

Back to contentsUveitis is the eye's response to a wide range of intraocular inflammatory diseases of infectious, traumatic, genetic or autoimmune aetiology. The end pathology results from the presence of inflammatory cells and the sustained production of cytotoxic cytokines and other immune regulatory proteins in the eye.

Trauma-related uveitis may result from a combination of microbial contamination and accumulation of necrotic products at the site of injury, stimulating an inflammatory response.

Infection-related uveitis may produce inflammation through the immune reaction directed against foreign antigens, which injure the uveal tract vessels and cells.

Autoimmune uveitis may result from immune complex deposition within the uveal tract.

Recent research has introduced the concept of 'molecular mimicry', where an infectious agent cross-reacts with ocular proteins. This triggers an inflammatory response.

How common is uveitis? (Epidemiology)58 9 5

Back to contentsAnterior uveitis is the most common form in the UK.

The prevalence of uveitis is variously given as 25-50 per 100,000 persons, with the mean onset at 30.7 years of age.

Most people who develop uveitis are aged 20-50 years.

Roughly 5% to 10% of these cases occur in children under the age of 16.

The epidemiology of uveitis varies with geographical location. Finland has one of the highest incidences of uveitis and this is thought to be because of the high frequency of HLA-B27 spondylopathy amongst the population.

Racial predisposition is related to the patient's underlying systemic disease (eg, HLA-B27 positivity in white people, Behçet's disease in individuals of Mediterranean origin).

The prevalence of each underlying aetiology varies with age group, race and gender. For example:

Children: juvenile idiopathic rheumatoid arthritis, toxocariasis.10

Young adults: Behçet's disease, human leukocyte-associated antigen B27-associated uveitis, Fuchs' uveitis.

Older adults: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome, herpes zoster ophthalmicus and, in the developing world, tuberculosis and leprosy.

Males: ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, Behçet's disease, sympathetic ophthalmia.

Females: Rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

Symptoms of uveitis (presentation)1

Back to contentsClinical features vary depending on the location of the inflammation. Symptoms may develop over hours or days (acute uveitis), or onset may be gradual (chronic uveitis).

Acute anterior uveitis4

Usually unilateral.

Pain, redness and photophobia are typical.

Eye pain is often worse when trying to read.

Progressive - occurs over a few hours/days.

Blurred vision.

There may be excess tear production.

Associated headache is common.

Not all symptoms may be present at the start of an attack.

Chronic anterior uveitis

Recurrent episodes, with less acute symptoms.

Blurred vision and mild redness are common, often with little pain or photophobia, except during an acute episode.

Patients may find that one symptom predominates (typically this is blurred vision). They tend to become good at spotting this early.

Intermediate uveitis

Painless floaters and decreased vision (as for posterior uveitis).

Minimal external signs of inflammation (such as redness or pain).

Posterior uveitis

Gradual visual loss.

Usually bilateral.

Blurred vision and floaters.

Occasional photophobia; however, general absence of anterior symptoms (pain, redness and photophobia).

The presence of symptoms of posterior uveitis WITH pain suggests:

Anterior chamber involvement (panuveitis).

Bacterial endophthalmitis.

Posterior scleritis.

Orbital inflammatory disease.

Sudden bilateral loss of vision suggests VKH syndrome or sympathetic ophthalmia.

Panuveitis

Presents with any combination of the above symptoms.

NB: some types of uveitis are more insidious and may be asymptomatic (eg, that associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis).

Diagnosis of uveitis (investigations)4

Back to contentsA first episode of mild, unilateral non-granulomatous acute uveitis can be diagnosed by history and clinical examination alone. Laboratory investigation is not usually helpful if there is trauma or a known systemic disease, or if the history and examination do not suggest systemic disease.

Imaging may be helpful where there is posterior disease, in order to assess site or severity of posterior inflammation. Fundus fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are the commonly used techniques.

If history and examination are normal but the uveitis is granulomatous, recurrent, or bilateral, further investigations are necessary to look for underlying causes. The exact nature of the investigation is guided by clinical suspicion. Investigations might include:

FBC.

ESR.

Antinuclear antibody.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Rapid plasma reagin.

HLA testing.

Mantoux test.

Quantiferon gold.

CXR (to exclude sarcoidosis or tuberculosis).

Urinalysis.

Infectious workup - eg, depending on presentation, toxoplasma, Lyme disease, HIV, syphilis.

Laboratory tests on a sample of aqueous or vitreous may be helpful where infection or malignancy is suspected.

Examination

Fully dilated eye examination, including slit-lamp examination, is required to look for signs of posterior disease. The structures of the eye should be examined for diagnostic features and for features which may point to the underlying cause. Intraocular pressures (IOPs) should also be checked.

Visual acuity

Should be checked, may be reduced and, if so, is an important factor in management.

External eye

Lids, lashes and lacrimal ducts are normal.

Conjunctiva: typically 360° perilimbal injection, more intense close to the limbus; this is the reverse of the pattern seen in conjunctivitis, in which the most severe inflammation occurs further from the limbus.

Visual acuity may be decreased.

Extraocular movement: generally normal.

Pupils

There may be direct photophobia.

There may be consensual photophobia (typical of iritis: photophobia due to more superficial causes is typically direct but not consensual).

Miosis is common.

Epithelium and stroma

Look for abrasions, oedema, ulcers, foreign bodies.

Cornea

Look for:

KPs - inflammatory cells clumped together on the posterior (endothelial) part of the cornea as little white spots. KPs are characteristic of uveitis. When KPs appear large and granular or greasy, the uveitis is described as granulomatous.

Ciliary flush, a violaceous ring around the cornea, suggests intraocular inflammation.

Corneal oedema may be seen.

Lens

Lens changes may occur, most commonly posterior subcapsular opacity secondary to steroid use. These are not specific for uveitis.

Anterior chamber

In uveitis, severely inflamed vessels leak protein which clouds the normally clear aqueous. This looks hazy with the slit lamp. If severe, it disperses the light beam, causing flare.

White or red blood cells may be observed: the presence of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber suggests inflammation of the iris and ciliary body.

Blood cells: grading of blood cells in the anterior chamber is as follows:

0 - none.

1+ - faint (barely detectable).

2+ - moderate (clear iris and lens details).

3+ - moderate (hazy iris and lens details).

4+ - intense (fibrin deposits, coagulated aqueous).

Hypopyon may be present if there is significant inflammation. This is highly suggestive of diseases associated with HLA-B27, Behçet's disease or, less commonly, infectious uveitis.

Iris

There may be anterior or posterior synechiae on the iris as a result of inflammation. These have the potential to lead to secondary glaucoma.

Iris atrophy is a diagnostic feature of herpetic uveitis. Herpes simplex causes diffuse atrophy while herpes zoster typically causes sectoral atrophy.

Iris nodules may be seen in sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, VKH syndrome, sympathetic ophthalmia and syphilis.

Vitreous

Inflammatory cells in the vitreous, which may be clumped, suggest posterior disease.

Retina and macula

Associated retinitis causes a yellow-white appearance and poorly defined edges, often associated with haemorrhage and exudation.

Retinal vasculitis is usually seen in retinitis and may be seen in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and viral retinitis including herpetic infections.

Inflammation may lead to cystoid macular oedema, neovascularisation and macular holes.

Optic disc

Disc inflammation can occur even without other signs of uveitis. It usually appears as papillitis or disc oedema, neovascularisation, infiltration and cupping.

Sarcoidosis and leukaemia can infiltrate the disc tissue, producing an appearance similar to papillitis.

Intraocular pressure

IOP is most often decreased owing to impaired production of aqueous by the non-pigmented ciliary body epithelium. However, in some infective conditions (eg, herpetic uveitis, toxoplasmosis) it is increased due to the accumulation of inflammatory material and debris in the trabecular meshwork, trabeculitis, obstruction of venous return, and steroid therapy.

NB: if the history or examination suggests systemic symptoms, a further full physical examination is needed.3

Examination findings by anatomical type

Anterior uveitis

Visual acuity is often reduced.

The pupil may be abnormally shaped or of a different size to the unaffected eye.

Direct photophobia and consensual photophobia (pain on shining a light into the unaffected eye) may be demonstrated.

Circumlimbal injection (injection around the corneal limbus) is characteristic. This can be fairly localised but, as the uveitis progresses, the entire conjunctiva may appear red.

The main signs are seen in the anterior chamber:

The characteristic sign is the presence of cells in the aqueous humour. As you shine the slit-lamp beam through the anterior chamber, the appearance is of a shaft of light shining through darkness with bits of dust floating through it.

The severity of the uveitis is graded by the number of cells seen, ranging from 0 (no cells seen) to +4 (>50 cells seen).

The aqueous humour may become cloudy, with 'flare'. This appears rather like a shaft of light shining through a darkened, smoky room. Flare is graded from 0 (no flare) to +4 (fibrin deposition).

Other findings may include synechiae and keratic precipitates.

Intermediate uveitis11

Intermediate uveitis involves the anterior vitreous, ciliary body and peripheral retina.

Inflammatory cells in the vitreous are best seen with a slit lamp in the dilated eye.

Pars planitis refers to a subset of intermediate uveitis where clumps of white cells form globular yellow-white 'snowballs' in the inferior peripheral vitreous, and yellow-white exudates, band to form 'snowbanks'.

Posterior uveitis12

Inflammatory lesions may be seen on the retina or choroid. They may look yellow when fresh; older ones have a more distinct edge and a whitish appearance.

Inflammation of the retinal blood vessels (retinal vasculitis) may occur.

Oedema of the optic nerve may occur.

The inflammation may 'spill over' anteriorly so that there are inflammatory cells in the vitreous.

Scoring systems in uveitis

Various systems based on scoring a number of presenting clinical features have been proposed to assist in diagnosis and to standardise research findings.2 13 14 These include:

Location of inflammation.

Anterior chamber cells.

Anterior chamber flare.

Vitreous cells (present or absent).

Vitreous haze.

Differential diagnosis

Back to contentsAny cause of a red eye or visual disturbance should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Associated diseases 1516

Back to contents48-70% of cases of uveitis are idiopathic.

About 50% of patients with acute anterior uveitis are HLA-B27-positive.

Some infections are specifically associated with anterior uveitis, including herpes simplex and herpes zoster.

Non-granulomatous disease

This is associated with:

Sacroiliitis

Seronegative arthropathies:

Early sarcoidosis.

Early tuberculosis.

Early syphilis.

Drug-induced uveitis.

Traumatic uveitis.

Granulomatous anterior and posterior uveitis

These are associated with:

Herpes zoster virus.

In AIDS:

Cytomegalovirus.

Human syncytial virus.

Cryptococcosis.

Candidiasis.

Non-infectious causes of posterior disease

These include:

Behçet's disease.

Sacroiliitis (usually bilateral).

Lymphoma.

VKH syndrome.

Lens-induced uveitis.

Posterior uveitis - may also be associated with autoimmune retinal vasculitis.

Management of uveitis14

Back to contentsRefer people with suspected uveitis to an ophthalmologist within 24 hours. Do not initiate treatment for recurrent uveitis in primary care, unless asked to do so by an ophthalmologist: delay in appropriate management can lead to the development of significant complications and irreversible loss of vision

.

The aims of treatment are to control inflammation, prevent visual loss and minimise long-term complications of the disease and its treatment. There is no standard regimen: treatment is determined by the type of uveitis, whether it is secondary to infection and whether it is likely to threaten sight. Systemic drugs are reserved for sight-threatening posterior disease.

All patients with anterior disease and most with intermediate or posterior disease require treatment.

In chronic uveitis, treatment is usually indicated if the visual acuity has fallen to less than 6/12, or if the patient is experiencing visual difficulties.

Cycloplegic drugs

Cycloplegic-mydriatic drugs (eg, cyclopentolate 1%) are used to paralyse the ciliary body. This relieves pain and prevents adhesions between the iris and lens.

Steroids

Corticosteroids are used to reduce inflammation and prevent adhesions in the eye. They may be given topically, orally, intravenously, intramuscularly, or by periocular or intraocular injection, depending on the severity of the uveitis. Corticosteroids are reduced slowly, as withdrawing them too quickly may lead to rebound inflammation.

Many patients with unilateral chronic uveitis can be managed with topical corticosteroids, with periocular corticosteroids for macular oedema and visual loss.

Systemic corticosteroids are the mainstay of systemic treatment for patients with chronic uveitis: the usual indication for treatment is the presence of macular oedema and visual acuity of less than 6/12.

Immunosuppressors

These may be required for people with severe or chronic uveitis. These include methotrexate or mycophenolate, and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors such as adalimumab.

Ciclosporin and tacrolimus are also useful in selected patients.

Adjunctive therapy17

Infectious uveitis (bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic) is treated with an appropriate antimicrobial drug as well as corticosteroids and cycloplegics. See also the separate Chorioretinal inflammation article.

Severe or chronic uveitis may be treated with laser phototherapy, cryotherapy or vitrectomy.

Considerations prior to initiating treatment

These include:

Supporting evidence for specific treatments is sparse.

IOP should be checked and herpes simplex virus keratitis ruled out before starting topical corticosteroids.

Steroid treatment should only be initiated in consultation with an ophthalmologist.

Surgery 18

Surgery is considered in a small proportion of patients with severe or intractable disease or where a diagnostic vitreous sample is required (eg, to diagnose infection or malignancy).

Surgery may also be required for complications such as cataract, glaucoma and vitreoretinal problems; however, except in emergency situations, it should be contemplated only once the uveitis is controlled, ideally for at least three months.

Monitoring19

Back to contentsMonitoring is mainly by clinical examination but some investigations provide a useful adjunct:

OCT is helpful in looking for macular causes of worsening vision.

Fluorescein angiography is helpful in assessing retinal vascular involvement.

The only patient group currently screened for uveitis is children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Monitoring for efficacy of treatments, adverse effects and development of complications usually takes place in secondary care, but GPs may be asked to monitor patients on long-term treatments such as corticosteroids and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).1

Complications of uveitis

Back to contentsThe main complication of uveitis is visual loss as a result of one or more of the following list (the first two being the leading causes):3

Cystoid macular oedema.

Secondary cataract.

Acute rise in IOP, with or without glaucoma, either as a direct consequence of the inflammatory process or secondary to steroid treatment:

Some patients, especially those with a history of glaucoma, are prone to developing high IOP when on steroid treatment and require co-treatment to reduce it. Treatment can be stopped when the steroid treatment is stopped if there is no pre-existing glaucoma.

Vitreous opacities (inflammatory debris or haemorrhage).

Neovascularisation of the retina, optic nerve, or iris.

Macular ischaemia, vascular occlusions and optic neuropathy - can be complications of posterior uveitis.

Posterior synechiae are a common complication of anterior uveitis; they can cause blockage of the aqueous flow, leading to a rise in IOP. They also complicate cataract surgery.

Prognosis of uveitis

Back to contentsAnterior uveitis can be a self-limiting condition. The factors determining which cases will resolve without intervention are unclear.

With prompt and effective treatment, there is usually a good visual outcome (one study found that 91% of patients retain normal vision).

Relapse after a first episode of acute anterior uveitis is very common, particularly in patients aged 18-35 years. Recurrence rates as high as 66% have been reported, although there is a wide range in the number of reported attacks and the time period between them, which can be many years. 20

A 2025 study showed 72.2% of paediatric patients with arthritis associated uveitis experienced a chronic course of uveitis. 20.8% were asymptomatic, with intraocular inflammation detected only through routine ophthalmic screening.21

The prognosis of chronic granulomatous uveitis depends on the cause and on how promptly any underlying condition is recognised and treated.

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Further reading and references

- Uveitis; NICE CKS, March 2025 (UK access only)

- Deschenes J, Murray PI, Rao NA, et al; International Uveitis Study Group (IUSG): clinical classification of uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008 Jan-Feb;16(1):1-2.

- Duplechain A, Conrady CD, Patel BC, et al; Uveitis. StatPearls, Aug 2023.

- Xie JS, Ocampo V, Kaplan AJ; Anterior uveitis for the comprehensive ophthalmologist. Can J Ophthalmol. 2025 Apr;60(2):69-78. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2024.07.013. Epub 2024 Aug 8.

- Gutteridge IF, Hall AJ; Acute anterior uveitis in primary care. Clin Exp Optom. 2007 Mar;90(2):70-82.

- Harthan JS, Opitz DL, Fromstein SR, et al; Diagnosis and treatment of anterior uveitis: optometric management. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2016 Mar 31;8:23-35. doi: 10.2147/OPTO.S72079. eCollection 2016.

- Xu H, Rao NA; Grand Challenges in Ocular Inflammatory Diseases. Front Ophthalmol (Lausanne). 2022 Feb 17;2:756689. doi: 10.3389/fopht.2022.756689. eCollection 2022.

- Agrawal RV, Murthy S, Sangwan V, et al; Current approach in diagnosis and management of anterior uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010 Jan-Feb;58(1):11-9. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.58468.

- Guly CM, Forrester JV; Investigation and management of uveitis. BMJ. 2010 Oct 13;341:c4976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4976.

- Solebo AL, Kellett S, McLoone E, et al; Incidence, sociodemographic and presenting clinical features of childhood non-infectious uveitis: findings from the UK national inception cohort study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2025 Jul 22;109(8):955-961. doi: 10.1136/bjo-2024-326674.

- Biju Mark J, Smit DP, E R, et al; Intermediate Uveitis: An Updated Review of the Differential Diagnosis and Relevant Special Investigations. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2025 May;33(4):522-534. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2025.2450473. Epub 2025 Jan 14.

- Paez-Escamilla M, Caplash S, Kalra G, et al; Challenges in posterior uveitis-tips and tricks for the retina specialist. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2023 Aug 17;13(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12348-023-00342-5.

- Davis JL, Madow B, Cornett J, et al; Scale for photographic grading of vitreous haze in uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010 Nov;150(5):637-641.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.05.036. Epub 2010 Aug 16.

- Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT; Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Sep;140(3):509-16.

- Martin TM, Rosenbaum JT; An update on the genetics of HLA B27-associated acute anterior uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011 Apr;19(2):108-14. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2011.559302.

- Huang XF, Brown MA; Progress in the genetics of uveitis. Genes Immun. 2022 Apr;23(2):57-65. doi: 10.1038/s41435-022-00168-6. Epub 2022 Apr 4.

- Koronis S, Stavrakas P, Balidis M, et al; Update in treatment of uveitic macular edema. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019 Feb 19;13:667-680. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S166092. eCollection 2019.

- Musat AAM, Zamfiroiu-Avidis N, Stefan C, et al; Surgical Management of Complicated Chronic Uveitis: A Case Report. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2025 Jul-Sep;69(3):455-459. doi: 10.22336/rjo.2025.71.

- Ratay ML, Bellotti E, Gottardi R, et al; Modern Therapeutic Approaches for Noninfectious Ocular Diseases Involving Inflammation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017 Dec;6(23). doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700733. Epub 2017 Oct 16.

- Natkunarajah M, Kaptoge S, Edelsten C. Risks of relapse in patients with acute anterior uveitis. The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2007;91(3):330-334. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.083725.

- Li L, Zhang JM, Deng JH, et al; Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2025 Aug 18;19:2813-2820. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S529421. eCollection 2025.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 9 Aug 2030

10 Feb 2026 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free